WRITINGS ON EDUCATION

“…It is a very difficult time to be a parent in a world that is changing so quickly. The tools of technology are now held by your children, who can manage things with your mobile, your laptop, your remote control at which you can only marvel. Peer pressure, the recession and competition can become an inordinate pressure for parents and children when they should be enjoying their formative years at school.”

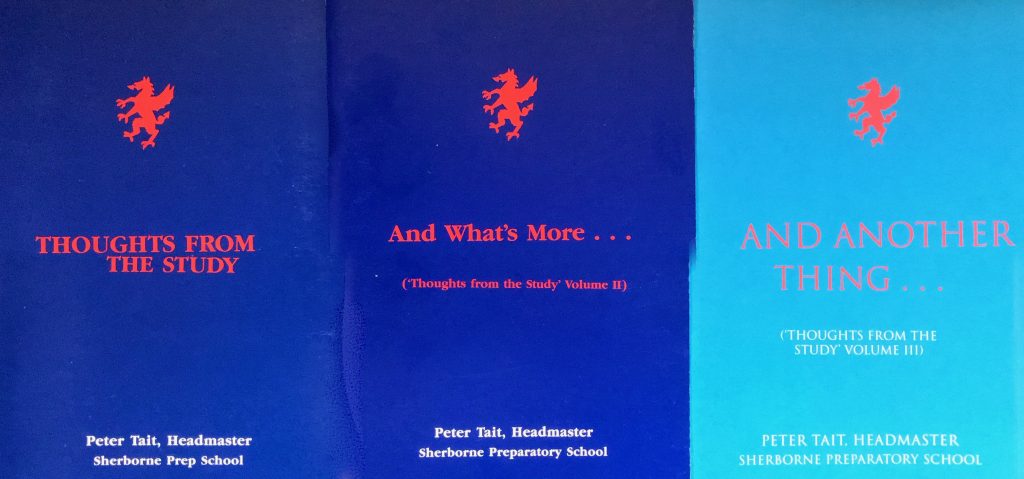

Since 2004 I’ve been writing on the joys and frustrations of running a school and of educating and raising children in the 21st century. If you would like to read the four volumes which include over 150 articles, please download below or go to www.petertait.education / articles:

Thoughts from the Study (2005 – 2007

And What’s More (2008 – 20010)

And Another Thing (2011 – 2013)

And Finally (2014 – 2015)

Not Again (2015 – 2016 (on-line)

Subsequent articles are included by year on www.petertait.education / articles

I have run inset sessions on strategic thinking and risk-taking for heads, coping with adolescence, presumptive history, school-wide strategy and developing school curricula. As an aside, I have also offered talks to students on Thomas Hardy based on my recent books and current research for any schools interested. Please contact me for details on ptait10@hotmail.com

Available from Civitas.org.uk – my contribution to the debate, titled “Unnatural Selection,” is on pp 152 – 166

LATEST BLOGS:

Applying the Lessons from Lockdown * (September, 2020)

‘University of Bristol research revealed anxiety levels dropped nearly 10pc in girls and 8pc in boys, between October 2019 and May, 2020’

‘Turns out not being taught for six months leads to better results. I’ve always said school was overrated.’ (Henning Wehn about GCSE results)

Several months ago, I wrote an article on what lessons we can take from the lockdown of schools. Many of the observations were obvious at the time: the loss of social spaces for children and the deleterious effects of little or no social interaction; the flexibility of learning times with on-line learning; the growth in the use and understanding of technology by parents, teachers and students; the inadequacy our current assessment system; the issues with funding and future financial implications; and the reduction (although not the absence) in teacher-student interaction. Other lessons were less obvious and some have only become apparent more recently, including the impact on mental health and the implications of relying so heavily on summative assessment. All told, they pose a considerable challenge for our schools as they re-open.

In our rush to get schools up and running again, it will be important, therefore, for school leaders and governors to spend some time looking at the effects of lockdown on children and the implications for future planning. It would be folly to ignore what we have learned and resort to the status quo and pretend nothing has changed when it has, and irrevocably so.

There is no doubt that the job facing heads and their management teams is very considerable and they will have their hands full dealing with the regulatory requirements involved in managing their response to Covid19; yet it is crucial that strategic thinking is not lost in the rush to get students and teachers back to work. One option for Heads, in light of their own brimming in-trays, is to identify members of staff who don’t necessarily have senior responsibilities, but who think about education and enjoy blue sky thinking to would relish the opportunity to try and measure the impact of the past six months and put it to good use.. A possible start to meeting such a remit could be through a questionnaire to gather information on the students’ experiences of lockdown. This could include questions on the perceived benefits (or otherwise) of learning on-line; whether it suited some subjects / students more than others; whether there are enough resources available; whether they feel safer and less stressed; and whether they felt some on-line courses suited their own learning. And then they could get their teachers to do the same.

It would be a surprise if the feedback didn’t prioritise the loss felt from not being able to interact with their peers and may proffer some suggestions as to how this and their distance learning could be better managed in the future. It could be that the role of schools is subtly re-defined, with more community involvement by capitalising on better communications and links between home and school; it could be that students will want blended education to be a part of their future and are eager for more breadth in the curriculum and alternative ways to study.

The implications for schools are huge. How to tap into this enhanced network of student-parent-teacher to assist feedback, community learning, reporting and pastoral care; how to provide a better and broader on-line provision (which may involve the employment of subject tutors and facilitators as distinct from classroom teachers); how to make schools less stressful for those who struggle socially and academically; how to structure the school day (later starts, more flexible lessons); whether new skills / subjects should be prioritised and whether, at some levels, some subject boundaries should be dismantled altogether (history + geography + sociology + economics + ecology could well be linked together as social sciences); how schools can be more environmental and sustainable – and then include these lessons into the curriculum; and to examine how to improve our offering to students who, because of learning or other difficulties, struggle to access the curriculum in the classroom. These are just some of the most obvious questions.

All of this would help inform SMTs / governors for future planning. Yes, schools are much more than test results and the absence, with very few exceptions, of schools claiming bragging rights this year from their examination results was a godsend. Governors are right to acknowledge the hard work of teachers and schools to create new learning and teaching environments, often in the face of public and government criticism, to ensure schools can re-open on time. But in our rush to get life back to normal, we need to look at what we have learned and apply the lessons of the last eight months. We can’t go back. We just need to ask again, are we providing the best education we can for our children – and if not, what do we need to do better

(*’Lessons from Lockdown’ 6 May, 2020 http://education.petertait.education)

Oxbridge and All That (November 2017)

The contention late last week by David Lammy, the one-time Minister of Higher Education, that Oxford and Cambridge Universities are not doing enough to widen the diversity of their entry was met with the predictable rebuttal by alumni of the two universities as well as from current students. They pointed, instead, to the failure of schools and teachers for not nurturing student aspirations in what is now becoming a familiar cycle of blame.

One current student who took up her pen to write on the debate talked of demystifying the Oxford experience and showing that people attend the university are ‘just like them.’ She didn’t quite give a lie to the idea that the two universities are the place where the cleverest people go or debunk the idea that clever people are better equipped than anyone else in the workplace, other than to make a whole lot more money through their working lives (estimated at £200,000 over other Russell Group graduates, courtesy of the brand name). Clare Foges commented in one article on the subject that the issue is not to break more people into Oxford, ‘but to break the Oxbridge stranglehold on the best opportunities.’ Perhaps the decision of one leading financial services firm, Grant Thornton, in 2013, to stop giving jobs based on academic criteria is a ray of hope. Four years on, it has found that four times as many appointees selected from the 10,000 applications a year who would not have met the company’s previous criteria based on grades and references have made their elite group (the Games changers) compared to those who had met the original criteria.

Rather than blaming the universities or the schools, (or lazy employers, content with the name, for that matter), we should consider the historic relationship between the universities and schools. Traditionally, places at Oxford and Cambridge were secured by word of mouth, often the result of a communication between a housemaster or headmaster of a public school and a colleague at the university. The relationship was very close and a reflection of a hierarchical society where education was the preserve of the well-off and the gentry. Independent students, of course, are no longer are given places on who they know – indeed, they would argue it is now more difficult coming from a privileged background. Yet where we see this connection flourishing today is in the number of Oxbridge graduates teaching in the independent sector, where they often make up the majority of the teaching staff. Even smaller regional schools are likely to have a number in double figures. A significant smaller number choose to teach in state schools, often at Grammar Schools while there are signs that more are beginning to go outside their comfort zone to teach at comprehensive schools. In the vast majority of state schools, you might not find a single Oxbridge graduate. And why should that matter?

Rather than focusing on universities and schools, we need to unpick a whole history of class and expectations. The fact is that most independent schools are packed full of Oxbridge teachers sharing their DNA with their students. Many state schools have few / no such role models. One response I had to a twitter feed on the subject noted that at their comprehensive there was a part-time Cambridge Mathematics graduate who felt a student in Year 10 was a contender for Cambridge, adding hopefully, ‘very lucky. Hoping they stick around for 3 years!’ If it takes a part-time member of staff to make the connection simply on their own experience, as in this instance, we are in a parlous state in those schools where there is no provenance, no tradition, no historic connection between school and university.

Of course, many would say why does it matter, all this fuss about Oxbridge. Apart from making sure that education at all levels is open to all, and however much we disavow the idea, the composition of the student body at both universities is seen as a barometer of social mobility. Unless we get an influx of Oxbridge graduates opting to teach in the state sector, it is going to be difficult to change behaviours. People aspire to what they know and often only feel comfortable passing on their own experiences and information. Perhaps if employees can see that clever people are not always equipped with the aptitude, character and skills they actually want, then Oxbridge might start to be seen as just another option, not just for the cache of having been there.

Modelling for Life (October, 2017)

‘The younger generation isn’t so bad. It’s just that they have more critics than models.’

Children are very perceptive. Often, what they might not be able to understand intellectually, they sense intuitively, but invariably while young, they learn best by imitation, through what they see and experience in the home, rather than by what they’re told. Prince Charles is reputed to have said ‘I learned the way a monkey does – by watching its parents’ and that is true for all of us. After all, who else has such an overwhelming presence in our young lives.

The parent is sometimes oblivious to just how much a child absorbs from all they see and hear going on around them. Sometimes the first realisation only comes after an inappropriate word or comment uttered first in the privacy of the home is innocently repeated in company by one of their off-spring. by all that children hear and see. If parents use inappropriate language, drink excessively or smoke, then such behaviours are legitimised; if they spend their time looked into their i-phones, they can expect to be imitated. Nor at they safe in sharing their more personal opinions. Children’s honesty at school can often be disarming and little is safe with children when amongst their classmates.

The importance of parents providing an exemplar for their children can hardly be overstated. If children grow up in homes that don’t value books, then they are less likely to do so. If parents openly criticise their teachers, it is hard for children to respect them knowing what they think. The same applies if politicians or policemen are constantly derided in the home. Yet even more important are the little things children learn by imitation: valuing effort; encouraging sharing; manners; respect; appropriate behaviour; and talking up the value and importance of education.

As children grow up, the resolve of parents will be constantly tested. During adolescence, children may become contrary, on the one hand appearing very moralistic, judgmental even, especially where adults are concerned and yet seemingly prepared to push the boundaries in their own behaviour, ignoring the role models presented to them by family and friends (although, in reality, seldom drifting too far from the values their parents espouse). By their teens, they may be better able to make their own decisions and intellectualize the concepts of right and wrong, but even in those tremulous years, they still learn largely by imitation, often through challenging the status quo.

It is patently obvious that children need strong and reliable role models as they grow up by mirroring the words, attitudes and actions of their parents and those others who have influence in their lives. In order to educate our children in those preferred attitudes and values, we should reflect those same attitudes and values in ourselves and give them voice. We must be aware of what we say in front of children and the legitimacy we give to behaviours and actions through our own words and example. If adults talk disrespectfully of other adults, they cannot then expect their children to act and feel differently. If adults are fair and measured in what they say about others, that also will show through in their children.

Schools and parents need to be consistent and work together for if both are not singing from the same song sheet, then children never learn what is acceptable and what is not. This can be true of simple courtesies, like opening doors, writing thank you notes and being punctual, or some of the bigger things, like respecting the law and other cultures, peoples and societies. Children dislike hypocrisy and don’t like being told one thing and shown another. They revel in surety, in knowing where they stand. If they are untidy they don’t want to be told so by someone who is equally untidy. If their use of language is inappropriate or they are lazy, then they need to see the correct behaviours and standards in the actions of those who correct them as well as in the words. They respect strength and don’t always appreciate being defended when they know they’re in the wrong – as they occasionally are. Children’s honesty is transparent and often their worries and concerns mirror the opinions and views of their parents or guardians or, indeed, their teachers. And so the responsibility is implicit in all of us, to ensure that the way we present to our children is consistent with the values we want them to acquire and acknowledge that, in so doing, words alone will not suffice.

Children need models. They need be able to respect their teachers, their government, their police force, their town council, but respect has to be earned. That is why role models, whether sportsmen, like Rafael Nadal and Roger Federer or celebrities like David Attenborough or are a power for good. Children are good on imitation and if we want them to imitate the right actions and values, and grow up as we would want them to be, we need to be the people they aspire to – for if not, they will grow up reflecting the values and behaviours we most dislike in ourselves.

Classroom Discipline (Published in The Daily Telegraph, 29 June, 2012 under the headline ‘What’s the Answer to Classroom Discipline?’)

One of the biggest issues taxing the leadership of schools is that of classroom discipline. Nothing affects learning outcomes, school improvement, academic attainment or the morale of teachers more than constant, low-level disciplinary issues that eat minutes out of every lesson, hours out of every teaching week. It is a cancer that is increasing year on year and taking up more of our teaching time and school resources. According to recent a YouGov survey, pupils are potentially losing up to an hour of learning each day because of disruption in classrooms, equivalent to 38 days of teaching lost per year. Of all the impediments against improving attainment in our schools, none is more pressing.

In response to these concerns, the government recently commissioned an independent review focusing on behaviour in schools and whose findings were published earlier this year in the report ‘Creating a culture: how school leaders can optimise behaviour. Its brief was to offer individual schools ideas and exemplars of good practice by focusing on the importance of school leaders in optimising behaviour through with reference to more directed teacher training, by establishing clear routines and expectations for pupils; and by making better use of school resources and premises. The report scratched all the familiar itches: the importance of clearly understood rules and sanctions, internal inclusion units and exclusions, school charters and whole-school values, and technology and mobile phones with the central message being that schools need effective leaders to develop the right culture to deal with behaviour and the team to deliver it. The report’s author, Tom Bennett, uses a number of case studies, including Michaela Community School and its boot camp, Seymour Road Primary School where all staff are trained by an outside provider and King Soloman Academy in North London where the code of conduct is strictly enforced. Each school has its own way of approaching discipline and the case studies offer exemplars for other head teachers to adopt as required. It is all useful, sensible and, frankly, largely common sense and as guidance, will no doubt be useful for heads who lack the vision and wherewithall to address the issue on their own.

The problem with the report is that it was never intended as a panacea and its limited brief and lack of a wider context highlight the difficulties facing schools by placing inordinate pressure on school leaders who are already reeling under other constraints, including staffing. What it does not do, however, is address some of the pressing concerns facing teachers. Nowhere do we read about the alarming statistics that since April 2015 and the and the beginning of this year, 2,579 weapons were seized at schools. Nor is there any mention of the fact that according to an ATL survey conducted in 2015, over 20% of teachers had been subject to false accusations by pupils or parents- and it is getting worse. Parents, families and communities, a key constituency to a blanket approach to dealing with discipline, only appears on page 58 of a 62 page report – far too late.

In reading the report two things are apparent: one is that of finding sufficient outstanding school leaders with the ability and vision to implement change at time when schools are struggling to appoint head teachers. The second is the amount of time and resources required to deal with disciplinary issues including the provision of inclusion rooms speiclaised teachers and more targeted CPD advocated in the report at a time when per pupil funding is falling and schools are even reducing classes to make financial ends meet.

There is also a bigger picture in dealing at discipline and that is looking at how our schools are perceived and the gap between home and school and the mutual lack in trust and respect. An alarming statistic taken from a DfE survey is that only 53% of teachers felt that parents respected a teacher’s authority or supported themin their work while the ATL report argued that poor parental discipline was to blame and that “Poor parental discipline is leading to children always wanting their way. Unable to discipline children without a comeback has meant this situation . . . will escalate and good teachers will be driven out when they are most needed.” With teachers leaving the profession and parents abrogating their responsibilities by not backing their schools we have an untenable stand-off where too many parents have become their children’s advocates over often minor issues rathr than supporting the quality of provision and the need for discipline for the benefit of all.

Schools need to work more with their communities, but in improving discipline they need to look at what is going on with our children and, in particular, at the issue of mental health.

The problem is that schools are too often places where children have to be rather than want to be. By being forced into a system that is driven by data and league tables, schools have become adversarial and attritional to too many children. We should look at the relevance of what we are teaching to ensure that schools have a better connection with aspirations and opportunities. Perhaps by talking endlessly of good schools and bad schools and selection, we are adding to the problem. Perhaps we should be looking at making schools more fit for purpose and move away from the academic bias in our curriculum that mitigates amongst so many of the children with learning and behavioral difficulties. Perhaps more emphasis on vocational opportunities and on a broader education would help, instead of the recent focus on the Ebacc. The fact that we have a generation of anxious, self-harming, depressed children is hugely worrying. Good systems, strong leadership from heads and leadership teams as suggested in the report can make hugely significant differences in individual schoolss, but as well as addressing the symptoms of deteroiorating discipline, let’s focus on whether our schools are still connected to youth in a way the recent election suggests not, and whether what the schools are doing in the classroom is exacerbating the problem.

Politicians and Education – Who’s actually in Charge? (published in the Daily Telegraph under the headline, ‘Schools have become a bureaucratic nightmare – it’s time teachers wrestled back control’ 2 June, 2017)

With the General Election less than a month away, education is again in the spotlight. Invariably, we are being served the same old mix of pledges, policies and promises: Free school meals, more grammar schools, abolishing university tuition fees, getting rid of the post-code lottery, all trotted out with the short-term goal of enticing the voter. If we want to dig a little deeper to see what each party’s vision for education is beyond the election, invariably, we will be disappointed. There are no big ideas; no evidence, either, of long-term strategic thinking; nor are there any properly considered responses to the immediate problems of teacher recruitment and retention or on modifying what we teach to meet the changes in the world of work.

Apart from the obvious retort that without increased per capita funding for schools, everything else is compromised, we should remember that the single most important reason for the failings of our schools since World War II has been the fact that successive governments have shamelessly used education to advance their own interests. The result has been a constant stream of new policies and initiatives as political expediency and the personal egos of ministers have trampled all over the body education. In 2010, fifteen eminent professors wrote an open letter to all parties contesting the election urging that schooling should be depoliticized and that what happens in classrooms should no longer be micro-managed by government. Seven years later, if anything, the situation has got even worse with even more intrusive bureaucracy and meddling and yet, in the crucial area of strategy, of planning the future of education beyond a five-year parliamentary term, of sorting out how to turn every school into a good school, there is a deafening silence. If we go searching for a definitive view of what our schools will look like in ten years time, again, nothing. Nothing, also, about how schools will deal with their changing function in the next decade; nothing about how education might be delivered or what form new and sophisticated programmes of on-line learning will take and what infrastructure will be required; and nothing on how our schools and universities will respond to new technologies, artificial intelligence and a very significantly changed job market.

Planning future strategy is not, however, the job of politicians alone. In fact, in an ideal world politicians should be taking advice and instruction, not giving it. Instead, the answer to all of the above lies in large part in our schools. Invariably, the lack of targeted strategic thinking in our staff rooms is usually attributed to a lack of time and funding cuts – how can schools, for instance, justify time for heads and teachers to engage in strategic thinking when class sizes are rising and there are increasing educational and social concerns that need to be addressed? But try we must. Teachers are a vast, largely untapped resource in foreseeing trends and implementing educational change. Despite the pressures teachers are under, schools benefit when they provide the forum by which they can be heard (and most teachers actually like to be involved).

There are challenges that come with this. At present, too few of the main contributors to the education debate come from heads and teachers in state schools. Rather, it has been the heads of independent schools, with their more more limited range of reference that have had the greatest voice. Whether this is because they are having to constantly position themselves in a competitive marketplace or because they have more to say and less to lose by saying it, somehow we need to attract more voices from a much wider constituency.

What we urgently need is for schools to work out methods of encouraging research and debate within staff rooms; ways to encourage teachers to think more about their profession and their subject and what works and doesn’t work; we need to find the thinkers in our schools (and they can anyone, from dinner lady to governor) and tap into them. As always, the challenge for schools will be to find ways to engage their staff to think, debate (and even write about) education, knowing that if heads and teachers aren’t engaged in strategic thinking, then the hijacking of education policy by politicians and bureaucrats will continue. And Heads, whether in isolation, through shared practice or in peer- groups, need to set time aside for strategic planning in order to at least meet the future half-way. Because if they don’t drive the bus, there are plenty of idealists and theorists working outside of schools, who will.

You want to Teach? Try Tutoring! (published in the Daily Telegraph on 10 April, 2017 as ‘Teachers must be freed from the shackles of admin work in order to do their job properly’ )

Recently, as I listened to a teacher talking of his role as Child Protection Officer with its raft of responsibilities, I couldn’t help thinking how the skillset required to be a teacher had changed over the past decade. As he detailed his job with all its pastoral responsibilities, record keeping, referrals and time spent working with agencies, it became very obvious that this role had subsumed his other ‘minor’ role of teaching and had come to dominate his workload. It is a trend that can be seen everywhere in schools as more teachers are given other roles to sit alongside their teaching, including responsibilities for safeguarding, first aid, counselling, health and safety, data management, the internet or implementing the PREVENT programme. This is on top of the increased pressures that teachers are under from constant changes in curriculum and exam syllabi, for better differentiation of children’s needs, more personalised learning, better identification of behavioural and learning difficulties and meeting the raft of targets demanded by league tables and Ofsted, all of which have added hugely to their workload.

Last week, one of the directors of Teacher Toolkit, Ross McGill, looked at the diminishing amount of time that teachers spend in front of classes. He posed the question that by spending less time with children, ‘Am I becoming less of a teacher?’ While the debate focused on whether teachers’ skills are diminished by teaching less, what was also interesting was how his contact hours as a teacher had shrunk from 90% as a classroom teacher in 2000, to 72% as a Head of Department seven years later to currently 24% as a Deputy Headteacher.

Perhaps that is not so surprising, given the ladder of promotion although one suspects that in 2000 heads and deputies were still teaching considerably more; what is surprising – and concerning – is the amount of time that classroom teachers – where Ross was in 2000 – have seen their contact time eroded by this whole raft of other responsibilities they have been asked to take on. More is being asked of teachers and schools to deliver on subjects as diverse as budgeting, philosophy, the enviroment, sex and relationship education, survival skills (after a prompt this week from Bear Grylls) and most recently, for internet lessons and on-line responsibilities.

The pressures on teachers can be grouped in three key areas. First is the demand for more and more data and detailed record keeping, for more accurate tracking and measurement, recording and reporting – all of which have eaten into teaching time as target grades, league table position focusing on A* – C percentages, ALPS reports and OFSTED ratings have become driving forces for improvement; second is the impact of technology which has opened up learning opportunities, but has also created enormous challenges notably through cyberbullying as well as jamming the system with e-mail traffic; and third, through the extra social roles and legal responsibilities that schools have taken on to ensure children are safe, through safeguarding and child protection; that they are properly fed and supported emotionally and physically; and, amongst other recent initiatives, that they are protected from the influence of terrorism. Consequently, teachers have been required to learn a range of new policies and procedures delivered mainly through inset or training days (once the domain of classroom practice) at a pace that is almost unsustainable.

As the pastoral demands have become more and more time-consuming, substantially adding to teachers’ workloads, schools are looking at the grim prospect of reduced funding and staff cuts. The fact that teachers are so often committed to teaching to the test (and scratch the surface of any lesson, and assessment is lurking there somewhere) takes away the room for exceptional teaching, teaching off-piste and encouraging initiatives, but this is not as it should be. New initiatives to change the face of teaching such as pupil premium are held back by lack of funding and unrealistic targets, while attempts to change the way we teach through collabarative teaching and project based teaching are compromised by lack of time and resources.

Undoubtedly it is less complicated in the independent sector as Shaun Fenton, Head of Reigate Grammar pointed out after moving from a highly successful career in state education: ‘When I moved to the independent sector I realised that it was possible to do that so much more effectively without the compliance culture that comes from Ofsted — without the constant compromises that are necessitated by funding problems. Suddenly we could do the things I’d always wanted. It was liberating.’

For schools and heads, perhaps, but for teachers the same pressures remain, even exacerbated by an expection to coach sport or contribute to extra-curricular activities as well. It is a profession under seige, overloaded and underfunded and often misundersttod or unappreciated by the public. Little wonder that we read of more and more teachers quitting to teach overseas or to become private tutors, although I would suggest that the reasons cited which are usually workload and long hours may hide another fact – that it may also be that, as teachers, they just want to teach.

Discipline: The Elephant in the Room (published in the Daily Telegraph on 20 March, 2017 as ‘Waning School discipline is the elephant in the classroom’)

‘Only the disciplined are truly free.’ Stephen Covey

On Tuesday, Government launched a five week consultation period on its guidance for expelling and excluding pupils, inevitably focusing on the process and the need for schools to meet their legal responsibilities. While this may be seen as a predictable response to the increase in expulsions and exclusions over the past three years, it is also, a symptom of the breakdown in discipline in many of our schools with the most common reason cited for both permanent and fixed period exclusions being ‘persistent disruptive behaviour.’

Few things eat away at the well-being of staff to teach than the disruptive student; however, like so much guidance and dictat on education, the current consultation document yet again concentrates on the effects rather than the causes of the problem. In the light of the new guidance, however, it is pertinent to ask why schools are not better supported in dealing with disruptive behaviour at an earlier point in the cycle, whether by extra staffing, legislation or other means. Over many years now teachers have been compromised in areas of discipline and their authority eroded while students, conscious of their rights, have often used them as a justification for errant behaviour, too often supported by their parents. While a number of parents are calling for more discipline in our schools, many others are busy criticising teachers and failing to support decisions of their schools. And yet, it is only by an accord between school and home that discipline and behaviour can be addressed and steps to be taken to address disciplinary issues at the source – which is as often ats not, at home.

Late last year, several articles about Michaela Community School appeared in the national press, prompting considerable debate. The School, under the leadership of Head Teacher, Katharine Birbalsingh, has a reputation for its uncompromising stand on discipline. Her philosophy of education, outlined in the book ‘Battle Hymn of the Tiger Teachers: The Michaela Way’ raised the hackles of libertarians, educationalists and parents up and down the country with the school’s ‘no excuses’ policy and its uncompromising insistence on standards described by her critics as the anthesis of what schools should be. Further, by stifling creativity and individuality the School was described as a joyless throw-back to education in the Victorian age.

Yet for all the criticism directed at the School, there were an equal number praising the stand it had taken, parents whose own children’s schools were constantly disrupted by students who appeared out of control in an environment where they were neither appropriately managed nor sanctioned.

Stepping back from the debate, it is indubitably true that falling standards of classroom discipline and the dilution of time in which teachers can actually teach are major impediments to learning and teaching, as well as being instrumental in driving large numbers of teachers from the profession. Above all else, schools should be about the quality of engagement and maximising teaching time and when a large proportion of lessons are given over to issues of classroom management rather than to teaching, it is invariably the students who will suffer. It is not more lesson time that is required, but more teaching time.

Children need order and structure in their lives. All schools work to provide this by instilling self-discipline through encouragement and example, by giving their students a sense of purpose and clear guidelines as to how to conduct themselves. Sometimes, however, students need to be called to account, to realise that they are part of a community whose attendance at school is to learn and that they have no right to deprive others of an education.

In this, pity the teachers who have been widely derided by the public, disempowered by legislation and hung out to dry by parents. Of all the threats facing teachers, one that has taken ever greater prominence in recent years, is that of their own safety, whether from physical or verbal attacks. In 2015, according to a survey undertaken by the Association of Teachers and Lecturers (ATL), over 20% of teachers had been subject to false accusations by pupils and over 12% by a parent or family friend. Poorly supported by the lack of specialist help available to deal with problems of children with behavioural problems or violent, unruly or disruptive behaviour, rendered powerless to deal with miscreants and subject to criticism by all and sundry when they do try to do so, they are in an invidious position.

This is particularly chastening when we consider that we live in a age when parents are demanding more and more from schools to whom they have handed over many of their traditional roles and responsibilities, most recently that of relationships and sex education, but also, importantly, in educating children about the internet when parents have dropped the bundle. And yet, instead of working with the schools, too often parents have become their children’s advocates over issues to do with uniform or hair length, the lunch menu or why their son / daughter didn’t get the main role in the school play. Of course, schools do not always get it right, but always attacking schools and teachers, especially for the small stuff, instead of supporting them to improve the standard of learning and teaching is not, I would venture, the best way forward.

There is no doubt that children learn best in an ordered and well-managed classroom and that if they are not able to manage themselves through employing a modicum of self-discipline, then some external moderation should be used until they are able to do so. It is an abrogation of responsibility for the government, for local authorities and school boards not to address the issue of discipline in the worse performing schools before setting out to create, as the Prime Minister has vowed to do, more ‘good school places.’ Parents, also, need to think about what they want for their children before championing their often errant offspring. The same ATL report of 2015, stated that “Poor parental discipline is leading to children always wanting their way. Unable to discipline children without a comeback has meant this situation . . . will escalate and good teachers will be driven out when they are most needed.”

In helping schools set standards often neglected at home, a good place for parents to start is in front of a mirror. After all, education is not about ‘them’ and ‘us’ or cheap point-scoring – it is about improving the future life-chances of all our children.

How will our education be Judged in twenty years? (published in the Daily Telegraph on 6 March, 2017 as ‘Now sex education is compulsory, it is time to prepare students for real life)

The announcement today that classes on relationships and sex education are to be rolled out across all schools, is yet more evidence of the extent to which the roles of schools and teachers have changed over recent years. Undoubtedly, there will be some teachers and parents who are nervous about whether the information being imparted is commensurate with the child’s level of emotional development or their readiness and ability to cope and understand it, while others, happy when the subject is in the hands of a skilled practitioner, may worry that not all teachers will have the ability or experience to handle such important and sensitive subject matter. While such an initiative is necessary due to the new threats faced by our children, we also know that in making our response, any response, we are in uncharted territory.

Responding to the epidemic of ‘sexting’ and warning of the dangers of pornography is hugely important and it may be dealing with the effects rather than the causes is where we find ourselves. It is, however, one more sign that education today is in an uneasy place, and that our schools are under ever-increasing social and economic pressures. In twenty years time, it may be that our generation’s response to a range of issues, academic and pastoral, will be judged as too often reactive and poorly thought through, merely patching holes or, worse, exacerbating existing problems. So much education policy is either catch-up or remedial, dealing with outcomes rather than causes. We still talk about improving the number of good school places instead of refusing to countenance the idea that there should be no such distinction between good schools and bad schools and adopting a much more structured formula to rank our schools according to need and to fund them accordingly. We still struggle to know how to deal with internet as it takes over the minds and bedrooms of our children; and we still haven’t worked out what will be the effect of our reaction, through excessive legislation and oppressive policies, to the pressures on the children in our schools.

There are some statistics we do know. One is that Britain is a world leader in family breakdown, with 60% of children born to unmarried parents experiencing family breakdown before their teenage years; worse, by the age of five, half of children in low-income households no longer live with both birth parents. What we have not yet fully measured is the impact this lack of stability has on the lives of the young (although teaching them about relationships, albeit sensitively, is a start).

We know that 1 in 10 children aged 5 – 16 years suffer from a diagnosable mental health disorder (around three in every class) and that between 1 in every 12 – 15 pupils deliberately self-harm.

We know that eating disorders, depression and emotional stress are on the rise amongst school-age children despite all our efforts to make their lives safer and to protect them from the dangers of the world and each other.

How we respond to these issues is the key. There has been a tendency to closet children, despite the knowledge that safeguarding is much more than building a wall which can make children even more vulnerable. In extremis, protecting children by making them fearful of adults and scared of their own independence is not helpful. Recently I read that ‘It’s actually pretty easy to protect children from abuse: all you have to do is keep them locked up without contact with other human beings until they turn 18.’ While this is deliberately fatuous (although some parents might not think so), many schools and parents have opted for a watered down version of exactly this, driving their children to the school gates in ever greater numbers, warning them of potential dangers and threats, however miniscule, in the school environment and beyond, challenging undue competition or any element of risk while placing their child’s self-esteem above their well-being. Just as we allow toddlers to build up imminity, whether by eating mud pies or the like, so children need to build up a resistance to the challenges of life by being exposed to them, in a secure and responsible way.

It is in the classroom that the judgement might be the most damning. If you go into a school anywhere and scratch below the surface, the majority of lessons are being driven by, and orientated towards, the process and actuality of assessment. Apart from the obvious constraints of limiting the breadth of learning, dampening curiosity and stifling ideas, children are increasingly required to operate under pressure, either explicit or implicit, (and one often palpable in their teachers) with everything focused on the test or exam. Having the test driving teaching rather than a methodology that encourages enquiry and questioning, teamwork, and independent study is clearly not producing the desired outcomes for the student; nor is it meeting the needs of the employer who bewails the skills students are leaving school with; nor universities who feel that in the dilution of curriculum, basic skills and the sense of intellectual enquiry have been lost. At the same time, the consequences of our assessment regime might explain the disillusionment of many students in our schools as well as the alarming increase in mental health statistics.

With society changing so quickly and the internet playing an ever greater role in young lives, schools are in an invidious position. I suspect the scorecard in twenty years time might give a pass for effort, especially in improving the safeguarding of children (although too often reactively and there is much more to be done still), but in terms of looking after the mental health and well-being of students and the success and relevance of their academic and personal education for 21st century life, I fear the report could be damning.

Let’s Start Again (published in the Daily Telegraph on 20 December, 2016 as ‘What has gone wrong with our schools? We need to get back to basics and start again.’)

‘Everyone who remembers his own education remembers teachers, not methods and techniques. The teacher is the heart of the educational system.’ Sidney Hook

‘20,000 pages of on-line guidance overwhelms Scottish teachers.’ Glasgow Herald headline, 1 December, 2016

What is wrong with our schools? What is this malaise that is affecting so many of our teachers and driving them from the profession? And furthermore, how is it, despite all our legislation and political push, we have ended up with a system that, according to PISA, still lags behind similar countries? By what process have we arrived at a system smothered in a mish-mash of requirements, wrapped up in endless policies and bespoke language that obfuscates and frustrates: in essence, a rampant bureaucracy that is slowly suffocating our schools. Why is it that so much of what schools are required to do has become unnecessarily complicated and time-consuming? Why can’t we get rid of the dross and start again?

To answer these questions, we need to strip our system back to the bones, to a simple, common-sense and pragmatic approach to education without all the meaningless debates about school types, whether we should call boys and girls ‘children (or he and she, ze as Oxford suggests). We need to get our focus back to where it should be, on the education of children (and adults, for education will need constant renewal in this brave new world). We suspect that much of what schools are now required to do is pointless, layered over the years, adding to, but never subtracting. But how can we do it differently? How can we change what has become an ever-more complex, label-laden, bloated and anachronistic system into something that actually works?

First, we must get teachers back to spending more of their time teaching children. We need to work at reducing the excessive, time-wasting requirements placed on schools and, if that does not work, then appoint administrative support to take care of the work that does not need to sit in the teachers’ domain, ie inputting data, filing, collecting, manipulating and extrapolating information, managing parent concerns and e-mail traffic. To make best use of our greatest assets, teachers must spend more time engaging directly with children rather than sitting in front of a screen, dealing with a surfeit of administrative tasks that can be dealt with elsewhere.

To make our schools work for all, we need to bury the myth of selection. Every time selection is mentioned, there is the downside, which is what happens to the rest, those who at eight years old or eleven or thirteen cannot jump over the bar, but who will be able to in time and need to compete with those who can? What we want, surely, is rigour for all schools, where streaming and setting through a semi-permeable membrane allows for each to be taught according to their stage of readiness and need. Rigour is not the preserve of selective schools; indeed, selective schooling often dilutes rigour, softens the edges and leads to complacency on both sides of the divide. What is needed in all schools is for children to develop a sense of purpose, through self-discipline, clear goals, outstanding teaching and an appreciation of the gift of education.

We need to revisit the whole rationale of inspections. Why are Heads Teachers perpetually frustrated and nervous about inspections? Why are they seen as ambushes? Why should Schools have to be subject to constantly changing, and often contradictory requirements? (I remember being told to put glass windows in dormitory doors one inspection (safety) and take them out at the next (privacy) Simplify, simplify! We all know just how spurious and petty inspections can be, with so many pointless requirements and reams of documentation that cannot possibly be managed by teaching staff – except that in small schools, without a bevy of staff members employed to deal with human resources, it actually is – and decry the waste of time and resources.

Safeguarding, Child Protection and Health and Safety have, likewise, become industries, generating work, necessitating the employment of armies of advisers, consultants, spawning inset days, conferences, articles and books. Of course, the safety of children must be a paramount concern yet, in many ways, our excesses have made children less safe. Constant tweaks, wasted days going over revisions of revisions, generic comments when there is nothing sensible to say, so much content, piled up and constantly changing does little for safety. Policies should not have to be tweaked by individual schools at ridiculous cost, often flying blind, advised by expensive outside agencies. Regulations need to be simplified so that inspections work for schools, not to justify the cost and excessive bureaucracy of an inspectorate.

Ideally, the key points (and there are usually only a few KEY points in each policy, i.e. who is the LADO, what do you do when approached by a child in confidence etc) should be on flashcards that can be carried about and referenced as appropriate. Safe-guarding is too important to risk losing the focus in the detail and yet the reality is we are in danger of doing just that. The same may be said of PREVENT which has created an industry of its own. And through it all, despite the excessive attention to detail, have we actually made our children safer: many fewer walk to school or take exercise; many are more risk adverse, have had their initiative and competitiveness stunted, are more dependent, more vulnerable, more unhappy than ever before. Somehow, we need to restore the balance. Let’s focus on areas that matter: the fact that nearly 19,000 children were admitted to hospital after self-harming last year in England and Wales – a rise of 14% over the past three years; the fact that 62% of 13 – 20 year olds have experienced cyber-bullying; or the fact that most children have begun using a mobile phone or are on-line by the age of eight. How have we protected them? How have we taught children appropriate values and behaviours so they don’t use the internet as a weapon of choice? How have we protected them from themselves?

Which leads us onto the elephant in the room, technology. Having wasted billions experimenting with anything from raspberries to whiteboards, we must revisit the place of the internet in our schools –quite distinct from the teaching of computer science and coding.

Marc Goldman recently wrote ‘I am increasingly concerned about the ubiquity of computing in our lives and how our utter dependence on it is leaving us vulnerable in ways that very few of us can even begin to comprehend.’ We need to look at the whole way we teach about the internet. Here we should consider a new subject – ‘The Internet and Social Media’ or suchlike – that teaches children how to use the net, and includes such sub-topics as using social media, identifying fake news, internet safety, cyber-bullying, the dark web and how to use the net to its potential, all under-pinned by a robust, ethical framework. Without some rules, some self-regulation, we are placing our children in danger.

In teaching, we should focus on teaching and deal with the small stuff, such as handwriting, in the classroom, keeping learning support staff for those who have more significant learning difficulties. We should put more emphasis on writing, in sentences, paragraphs and essays, to learn how to reason, argue and communicate. And let’s take seriously the proposition that philosophy and ethics should be compulsory from a young age to underpin nanotechnology and science, to guard against the inducements of the Net. Teaching values and ethics, responsibility and community, is the best way to keep them safe and protected from the selfishness of money, power and prestige, which is what young children are inadvertently being tempted to pursue.

We need to make education more attractive and relevant for all and raise its profile (and promote it as a life-long commodity). To do that successfully, we must engage more with parents and guardians and educate them too – to say they need help and guidance is not condescending, but a reflection of the helter-skelter world they live in, assailed on all sides by so much misguided and contrary advice from parenting sites and magazines that cannot help but make them insecure in wanting to do their best.

And for their sake, let’s move children away from the centre of the universe, placed there by doting, well-meaning parents and put them back in their families, in their communities and other social groups so they learn to share, socialise and take some responsibility.

Let’s get rid of the shameful distinction between good school – bad school, in fact, let’s forget about school types and treat schools according to need. Let’s look at where we are spending our education pound, and work on training, procuring and looking after the best teachers. Let’s not get hung up on class sizes or resources and be properly cautious of all the extraneous advice offered by experts, the quality of in-service training we buy into and keep asking ourselves, ‘is this going to improve the education (or safety) of our children?” And we should celebrate those schools that demand more from their students through discipline and standards and stand up to those ‘experts’ who view such methods with opprobrium.

We should look after children by helping them through each stage of development and ask ‘is anything more likely to cause mental health issues than those experts who tell us children need to know every detail of drug abuse, death, disease and sexuality before they are ‘ready’ – yes, readiness again – and nothing of the joy and adventures of life? We should prioritise Mathematics and English, but not through testing alone which determines the learning process and ignores how learning – deep learning –happens; we should stop being in such a hurry by trimming our curriculum, removing the colour and floss, or by closing doors early through selection, separating children from other children for reasons of IQ or maturation and producing the stratified society that does us such harm.

We need simplified inspection frameworks; we need teachers to get back teaching; we need easily understood and simple guides to safeguarding and child protection, we need risk assessments to focus on real risks, not some meaningless compliance or box-ticking. We need to get rid of the legalese that permeates our schools, do a time and motion study and see how much time, especially teacher time, we are wasting. Let’s give inset days back to improving teaching rather than an endless succession of first-aid, fire-training, prevent and compliance courses. Let’s simplify our schools and get some rigour and pride back into the classrooms and make sure they are places that are both relevant to children’s needs and where teachers and pupils want to be. Let’s start again.

The American Option (published on the ISC Website, 1 December, 2016)

After sitting her A Levels at an English boarding school in the 1980s, Amanda Foreman was awarded an E for English – even after a re-sit. Not surprisingly, no British University made her an offer, leading her to look abroad for her tertiary study, not by choice, but by necessity. Yet a few short years later, after completing her under-graduate studies at Sarah Lawrence College in the USA, then Columbia University, she won a scholarship to Oxford where she completed a DPhil on ‘Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire’ (later to win the Whitbread Prize for best biography), launching her on a career as an academic and writer. What was it in the United States education system that allowed her to flourish? And, conversely, what was there in our system of assessment that allowed her (and many like her) to slip through the net?

One possible explanation is that some students take time to find their academic potential, to find out what they want to do or to learn what study is really all about. Another, more plausible, is that some approaches to tertiary study suit some students more than others and that for an increasing number, the breadth offered by American universities, particularly in the liberal arts, is much more appealing and relevant to them compared to the more rigid system we have in England. Even the process of application focuses as much on character as academic prowess, with the admissions process including essays and pieces of reflective writing an important part of the process.

While the cross-Atlantic traffic is still firmly in the UK’s favour, over the past decade the numbers of UK students going to study in the United States has grown steadily, and is now increasing by around 8% per annum. Each year, over 10,000 students are leaving to study at American universities, with the majority going to the prestigious Ivy League universities such as Harvard, Stanford and Yale, more than half at under-graduate level. As well, the number of students at UK universities studying abroad as part of their studies has soared by 50 per cent last year, a trend that seems likely to accelerate in the future. Even for students initially put off by the high costs, the very many generous bursaries and scholarships available at American universities have, on investigation, made it a realistic proposition

Two years ago, Sir Anthony Seldon, then master of Wellington College, Berkshire, suggested that students were being attracted by the breadth of the liberal arts curriculum, in which students take a range of subjects in their first two years rather than specialising in one discipline, suggesting that British universities should take note of a growing feeling that British degrees were too narrow.

“There’s an allure about studying in America and having a broader, liberal arts approach with greater focus on sport, music and artistic prowess. It is a more generous vision of what higher education can be rather than the utilitarian approach we see in the UK.”

For those who go to university with only a vague idea of what they want to do, being able to select their ‘Major’ after their first two years of study rather than at the outset has considerable appeal. As part of their liberal arts education, mandatory for all, students study a wider range of subjects in comparison to English universities, (more akin with the position in Scotland). Students are encouraged to take other courses to provide complementary skills and interests that designed to give students a greater breadth of knowledge. Hence, even if set on studying engineering, a student will receive a broad education in the liberal arts before specialization, something we may see as wasteful of time and resources, but which is fundamental to the American tertiary system.

At the recent Education Theatre, now an integral part of the annual Independent Schools Show in Battersea, one of the key talks centred around the process of applying to American universities. Without repeating the detail of the talk that can be accessed on the YouTube link below, or the difference in requirements (applications, for instance, have to be made to individual universities and need to start a good year earlier etc), there is a clear difference in the ethos and approach of the two countries in their approach to tertiary study. Not surprisingly, a growing number of schools are considering the option of American universities in all its diversity as they seek to offer the best advice for their students.

‘Charity should begin at home – but should not stay there (Philip Brooks) ’ (published in the Daily Telegraph on 22 November, 2016 as ‘Fundraising for charity should be commended, but schools must focus on more than cash and cake stalls’

‘One must be poor to know the luxury of giving’ – George Eliot

Every day through the mail we are besieged by charities, either at home or abroad, extolling causes that need our support. Good causes are everywhere, bewilderingly so, and the public conscience is swamped by the ever-growing numbers, all touting for their money. With around 160,000 general charities operating in the United Kingdom, with a combined income of around £37bn, charities are big business.

There is no doubt that schools are one of the prime targets for many charities. One only has to read the newspapers and websites to read of considerable amounts of money being raised by children for worthy causes. I know that schools I have been involved with have always taken pride in their charitable endeavours, often raising significant sums for different charities through a mixture of mufti days, appeals, cake stalls, donations, spellathons, marathons and the like. And that is fairly typical of most schools, as a constant stream of press releases and websites would attest. Surely, then, we can feel satisfied that we are doing our bit?

Quite possibly we are – or at least we do what we can without undergoing personal hardship, sacrifice or inconvenience. In other words we are doing what every affluent society does, giving away surplus money and goods. We seldom, though, give to the point of personal inconvenience or hardship.

Despite all the charitable giving, there is a danger that children are becoming desensitized by the sheer number of charities that confront them and end up feeling fatigued by a seemingly endless wave of disasters, diseases and afflictions. This feeling of helplessness is no doubt exacerbated when they can read that one in five of the UK’s biggest charities are spending less than half of their income on good causes. For a child, the world must, at times, appear to be a very bleak place.

In recent years, many of the young, encouraged by numerous celebrities imbued by a sense of idealism and social justice, have set up their own charities to address inequality, poverty or some specific cause, perhaps linked with saving a species of animal. Such initiatives should be commended, but with the health warning that charity should not just be seen as something best managed at a distance. Helping earthquake victims in Haiti, coffee pickers in South America, textile workers in Bangladesh or the starving in the Sudan are all hugely invaluable causes, but giving aid on its own is never enough. To be properly charitable it is essential that the sense of responsibility and compassion, the spirit of charity accompanies it and extends both to our own communities and others. It is about engendering the traits of simple kindness and thoughtfulness in our schools and communities towards those who are not so fortunate as ourselves in the world at large. It is about imbuing children both with the habit of giving and sharing and with a sense of responsibility about the world they live in. It is showing a willingness to listen and befriend those in our own increasingly soulless and fragmented community who may have enough to live on, but who crave company and opportunity, people often without hope, stranded in an emotional desert, perhaps the neighbour preparing to spend next Christmas alone.

Charity is not just about money and aid given; it is about intent. It is a well-known fact that those who have little, give, proportionately, much more than those who have a lot (it is estimated that the bottom 20% give away four times the percentage of income than those in the top 20%). Giving away excess funds is commendable, but charity should also be measured by commitment, empathy for those in need without discrimination or bias and making a personal effort, even if only measured in time spent. Which brings us to work days, sponsored projects, cake stalls and the like. Of course, anything that raises money is commendable, even if it doesn’t involve the child directly, but those parents that simply hand over money to their children do nothing to inculcate the habit. In our schools, we should try to encourage both.

The hope is with the next generation. They are more community-minded than we have been, more aware, more international in their thinking, more altruistic, guided as they are by a new wave of philanthropists who rightly inspire them. It is important that they do not come to think of charity as just an endless stream of good causes, for there will always be good causes; rather, we need to imbue them with the spirit of charity in their lives, a particular mindset so they will look charitably at those in their own country while also looking outwards to see what they can do to help others, as citizens of the global village.

‘Charity looks at the need and not at the cause’ – German proverb

The Value of Value-Added (published in the Daily Telegraph on 7 November, 2016 as ‘It’s No surprise that selective Schools get the best results – parents should look at Progress not Oxbridge places’ )

For families from abroad looking for schools in the United Kingdom, there are invariably two initial requests: first, how to get their children into one of the cache of well-known (and often heavily over-subscribed) schools; and failing that, to assess how any other schools suggested to them perform on the league tables. This is altogether understandable, first to seek out the known for the unknown and, second, to provide a recognised measure based on examination results. What is not obvious is that the vast majority of the high-performing schools are there because they are highly selective and need to be seen in the light of entry requirements that set the bar so high that getting into their schools at 13 years requires a standard at or above GCSE. This is not to say that their value-added is negligible, although it is likely to be constrained by the limiting process of selection, but what it does not tell you is the quality of their learning and teaching in comparison to other schools.

The challenge of establishing a dependable method to rank schools by value –added (ie the improvements made from a base score over a set period of time) has long been a target for educators trying to find comparative means to show how schools are performing relative to each other. In this, the Government is leading the way through its ranking of schools based on CVA (contextual value-added). Over recent years, value added tables for measuring progress between KS2 and KS3 and also from KS2 to KS4 have shown value added scores based around 1000 with measures above or below 1000 representing schools where pupils on average made more or less progress than similar schools nationally. This system was replaced, first on a trial basis in 2015 and now nationally by Progress 8 which measures how well pupils at any school have progressed between the end of primary school (key stage 2) and the end of secondary school (key stage 4), compared to pupils in other schools who got similar results at the end of primary school. This is based on results in up to 8 qualifications, which include English and Mathematics with the average Progress 8 score for ‘mainstream’ schools in England being 0.

In the independent sector, by comparison, while many schools subscribe to independent external moderators, such as ‘Alis’ to provide value-added analyses for their schools, there is less consistency in the gathering and use of data. While there is undoubtedly an appetite for this information to be used externally, the Centre of Evaluation and Monitoring at Durham University who crunch the data and provide the analyses, do so with the caveat that it is only to be used as a guideline for individual schools, and not for comparative purposes. Rather the focus of independent schools on the subject of ‘value-added’ has taken a different tack. Recent research commissioned by the Independent Schools Council from the Centre of Evaluation and Monitoring at Durham University compared ‘academic’ value-added between sectors – rather a different thing altogether and designed for a different purpose. Its findings, that ‘attending an independent school in England is associated with the equivalent of two additional years of schooling by the age of 16’ is helpful in promoting the sector, but not being able to see which schools are performing best based not on the basis of selection, but on the quality of their learning and teaching.

I recently attended a governors’ meeting at Wellington School in Somerset where the subject of exam results was discussed. Despite the enviable feat of achieving five Oxbridge places (sadly, still used as the gold currency for marketing results by many independent schools), refreshingly, the focus of the discussion was not on the success of a few, but on value-added, on how all their students had fared and how much they had improved over their time there. Of course, it is important that all schools show that they can achieve excellent results with their brightest and most talented students, but what got the teachers excited here was the improvement shown by their students and just what they had been able to achieve for each individual. This is what education is all about – maximising potential, whatever the starting point, rather than selecting the most able and duly celebrating their achievements.

Working in a school that adds value to all its students from a wider base, teaching a range of abilities is what education is all about. Being in a more selective school is no guarantee of better exam results; conversely, attending a school where children mix with a wider range of abilities and backgrounds, and crucially where they also have the opportunity to move up (and down) the order as they mature, can often be hugely advantageous. Without proper data for value-added, however, we cannot be adamant either way.

There is a great deal of satisfaction seeing students come through the ranks, by dint of hard work, to see the late developer hit his or her straps, or the student in whom one or more teachers have invested considerable time, doing well. This is why teachers teach. To make a difference. This is the joy, not of putting a cherry on top of a well-baked cupcake, but to take responsibility for, and be involved in, the preparation from a much younger age / stage – and having that progress accurately measured and acknowledged.

Building on from the bottom up (published in the Daily Telegraph on 11 October, 2016 as ‘Our Obsession with Hierarchy means Primary Schools often struggle to be heard’)

One of the most frustrating aspects of being a prep school head was the way that our schools always seemed in thrall of their senior colleagues, always deferring to their opinions and decisions, waiting to be told what was happening before reacting – even to such unfriendly gestures as senior schools moving to a Year 7 point of entry or timing their scholarship exams ever earlier in the school year – and our reliance on them to take leadership of the independent sector. This is in no way to disparage the senior sector; to the contrary, I am sure it is not a state of affairs they seek (after all, they have their own battles to fight with the constantly changing national qualifications and pressure to get students from A to B). Indeed, I am sure they would welcome a more active and vocal prep school voice.

In suggesting that prep schools take a more prominent role in the education debate, I am mindful of the pressure they are under from the marketplace and workloads that have increased disproportionately in recent years. But that should not distract from the need for prep schools to become more in such issues as the shape and content of the curriculum, the teaching of values and languages, blended learning and technology, social education and well-being – and not being afraid to opine on secondary and tertiary issues as well.

Apart from the fact that it is in the junior years that children learn most of what they know and where children spend the majority of their school years, this is the time when teachers can focus on children, free from national exams that strangle so much initiative and creativity. This is when children can learn independence, the purpose of education (which is to embed the habit of life-long learning), to teach values, how to study and how to develop proper work habits and attitudes; a time to ask questions, however tangential, before the time comes when they are told, hush, it’s not on the exam syllabus so it doesn’t matter.

Senior schools, with league tables hanging over their heads and encouraging even greater selection, with all its social consequences, have not always been the best exemplars, leaving prep schools with the quandary ‘how do you get pupils to reach the level demanded by some scholarship examinations while wanting to offer an all-round education and ensure children’s well-being? How do you build foundations both for those schools that start at the ground floor and those who aspire to start eight stories up?’

Prep schools should be asking why are there not more prep school heads on senior governing bodies (and for that matter, why are there not more pre-prep heads on prep school boards and senior school heads on university councils?) How many prep school heads ever speak at senior school conferences compared to the number of senior heads who regularly appear at prep school conferences to tell us what we should be doing (do we really need senior heads to tell us about values and social skills, the importance of breadth and education for education’s sake when they have often been the impediment to this happening in the first instance?)

Prep schools need to stop looking up to their senior colleagues and being so deferential. They need to be more involved in sharing ideas and take a lead in where education is heading. They need to be proactive, not reactive; leaders rather than followers; innovators rather than bastions of tradition for no good reason other than that is what is expected of them – until no longer needed. They need to promote their own strengths and the importance of their role, not as ‘preparatory’ to another stage of education (for all education is preparatory), but as the most influential, most important and most dynamic time in a child’s life.

This is a challenge for prep schools. Where possible, schools should be speaking out on the issues that affect our children (female mental health being one currently in the news), by standing up and saying what they think to be the right way forward, from their experience of teaching children at different stages of development and of the learning process, for a raft of social and academic reasons and for the well-being and future mental health of their pupils, without fear of ruffling feathers or being seen as speaking out of turn.

What are Schools for and where are they heading? (published in the Daily Telegraph on 27 August, 2016 as ‘School’s out forever; New Zealand’s plan to allow children to study on-line raises the question, ‘what are schools for?’)

As we debate whether the increase in the number of grammar schools will improve social mobility, or even if selection at the age of eleven is a good thing or not, education elsewhere in the world moves on. In a presage of the future, last month the New Zealand Government outlined legislation that will allow any school-age students to enroll with an accredited online learning provider who will have the responsibility for determining whether their students will need to physically attend for all or some of the school day.

The radical change that allows any registered school or tertiary provider such as a polytechnic or an approved educational body to apply to be a “community of online learning” (COOL) has met with an equally cool response from the primary teachers’ union. As well as potentially undermining their own livelihood, the idea of young children learning some or all of their lessons out of school, has prompted educationalists to revisit the question ‘what are schools for?

On-line learning is hugely important in making available subjects to students that schools could otherwise not offer, or for those unable to access school or university, for social, health or geographic reasons. Yet while a part of everyday life, its extensive use in schools, particularly primary schools, has been greeted with caution. Not surprisingly, therefore, the suggestion that children not be required to attend school for part or all of their learning has been seen as having huge ramifications for families concerned with the monitoring and supervision of their children. While one assumes common-sense will prevail and that the Government will insist that most remote learning takes place in a supervised physical community, (perhaps dependent on age), it invariably poses the question about what will be the role of schools in the future as more and more subjects and courses, delivered with increasing levels of sophistication, will become available on-line.